...

| Expand | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Consolidation is the process whereby a brain state in active or working memory is stored in long-term memory. This process modifies synapses on the dendrites of neurones. After retrieval of the memory, a similar process, called reconsolidation occurs whereby the old memory is altered and replaced by the new memory. Multiple retrievals and reconsolidations may be needed to build an accurate chunk. It seems we are not prompted to reconsolidate

Both consolidation and reconsolidation happen during sleep, so we can’t possibly know what a learner has learned during a lesson. We must wait for at least one nights sleep, to find out what has become learning and what has not. It seems that if recall is too easy, reconsolidation won’t happen at all or make a perceivable change in long term memory. This fits with Bjork’s desirable difficulties. It seems that by its very definition reconsolidation can’t happen at the end of the lesson where the skill is taught, because the learner hasn’t had a sleep so hasn’t even consolidated the learning. |

...

Contrary to our expectations, feedback is better given after one nights sleep, than directly after an error. It seems that if we give feedback on the day of the error, we may not be as effectively triggering reconsolidation - see (2) above - that is we are not as effectively triggering the brain to change chunks in long-term memory. On the other hand, if we leave feedback for too many days, then feedback is not as effective as it could be either.

...

The learner has built an incomplete chunk in long-term memory - despite timely practice layers being small and therefore easier to learn, sometimes the learner will need more support to build a chunk - the teacher, via feedback-dialogue, should work with the learner to find what is missing and help the learner fix it. See also (5) fading scaffolding, for more about this. We recommend assessing rather than marking of assignments, to assist with this. With marking, the teacher might write a note to the learner, showing the missing bits, but with feedback-dialogue, we help the learner add the missing bits to the chunk, ideally via questioning rather than telling.

The learner has not replaced/adapted an incorrect chunk built some time ago, with a new/adapted chunk in long-term memory. This is different from 1. in that the chunk to do the old incorrect method hasn’t been overwritten, despite perhaps a new chunk being built in the lesson. So here we are working on changing the trigger i.e. the learner choosing the new correct chunk, rather than the old incorrect one. The best way to do this, is to offer a reason why the old incorrect one is incorrect, that chimes with the learner’s understanding.

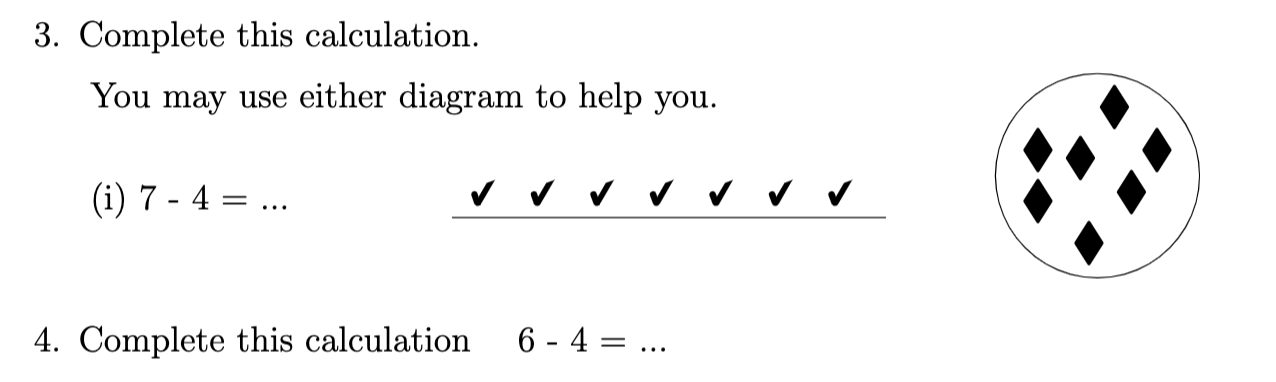

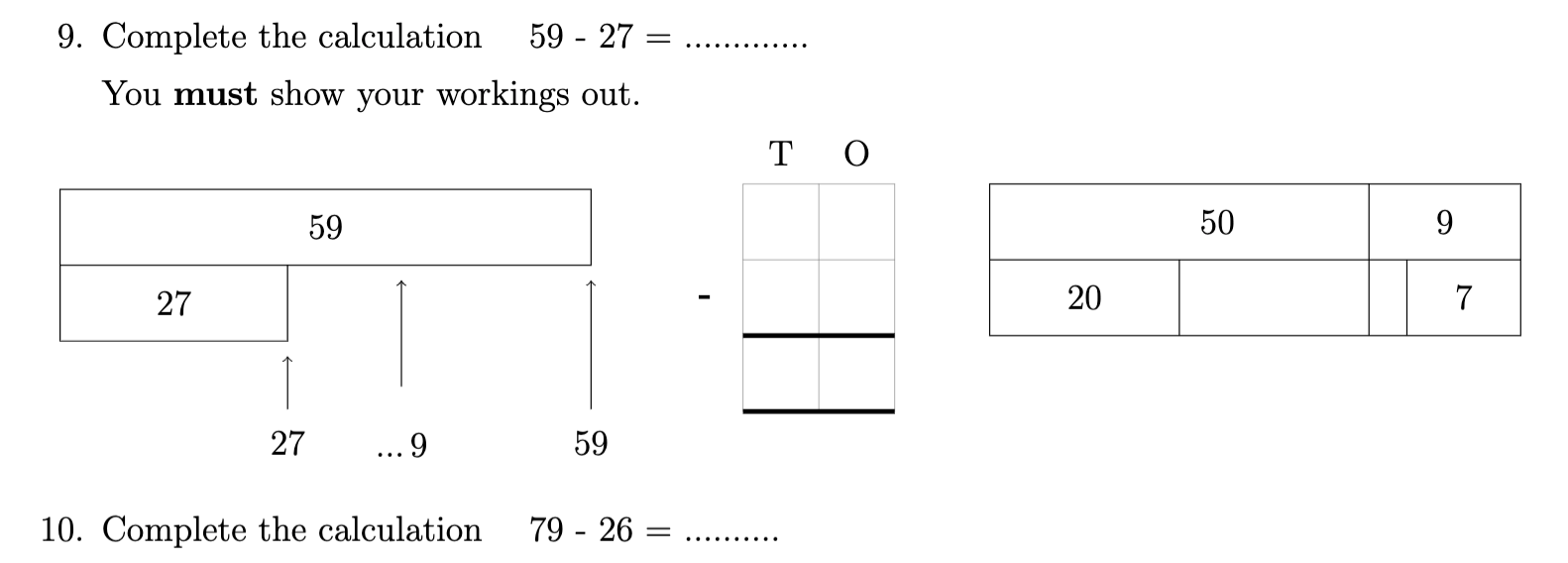

The learner is still reliant on some of the “unacknowledged scaffolding'' of the lesson e.g. placement of workings out on the page or use of a diagram etc. See (5) fading scaffolding, below for more about this.

The learner has misread the question or poorly applied their numeracy skills when answering the question. This is likely to be due to working memory overload - all learners, even the most able A level maths learners experience it. As they are learning and working through something new and hard, they are unable to accurately apply skills which are usually easy for them. I sometimes describe this effect to students as their brain isn’t very good at easy thinking and hard thinking at the same time. The best we can offer learners as they practise, is that they can look through their workings out for accuracy periodically. Sometimes I suggest they write “check for accuracy” on the answer line, as an aide memoire, for when they think they have solved the problem. We need to encourage learners to realise that making “silly mistakes” is often a sign of hard learning going on, not a sign that “they can’t even do the easy maths”.

...

The difference between being able to answer questions in a lesson, where all the questions require the same, recently learned skill, and being able to answer the interleaved retrieval practice questions within the learners assignment is a little like the difference between swimming with and without a floatfollowing a recipe and being a creative chef. As teachers we are often unaware of how much scaffolding is in the classroom when we are teaching a topic e.g. notes on whiteboard, vocabulary fresh in learner’s minds etc. Additionally, in the lesson where teaching occurs, learners don’t need to use the triggers for their chunks in long-term memory, they just need to remember the topic of the lesson. Almost all the practice questions (except of course those in their timely practice assignment) that learners will do in the lesson, will be on the topic of the lesson.

...

“what diagram will I ask you to draw?”

“where on the page, would it be best to show on the side workings your working out?”

When we ask questions like this we help nudge the learner to replace the external scaffolding of lessons with their own internal scaffolding - i.e. a better/bigger/more complete chunk in long term memory. It is often clear, that that is what we are doing e.g. as as soon as we say “what diagram”, we see the “aha” look and the learner wants us to go away and leave them to get on, they know what they are doing. The diagram, often already has a chunk attached to it, in the learner’s long term memory.

...

We have to accept that selecting best learned later and hoping that “in class teaching and practice” in the next spiral of the curriculum, is unlikely to solve the problem - if the problem is - : the learner could answer practice questions in the lesson they were taught, but can’t recall everything the next lesson. As it is clear that rather than the problem is not being unable to apply the process but , instead the problem is being unable to recall to recall the process which is the problem.

Hence, we are unlikely to fix the recall problem, with another lesson - whether the lesson is next term or next year - when we tell the learner what to do (unless, there are parts of the process that are not yet mastered).

We are however, much more likely to fix the recall problem, by a few quick feedback-dialogue sessions, in the next few lessons, especially if we see what the learner can already recall and then help them add a bit more to the process or join existing processes together.

...

given - sign layers 3 and 4 | given - sign layers 9 and 10 |

At the moment, November 2022September 2023, the app can’t automatically swap between scaffold pair layers - but we plan to do this in the future.

...

was given. I don’t think many teachers would count this as problem solving, because we are most would calssify this as merely requiring learners to use a number of skills to perform a standard problem.

...